Cowboys and Comanches on the Great Western Trail: A Time to Heal

Former warriors from opposing cultures met in a tenuous peace as Texans, whether white, black, or brown, pushed their cattle past Doan's Store on the south side of Red River west of present Vernon, Texas, where a ford over what the Comanches called "the big sandy" made it easy to cross onto the Kiowa, Comanche, Apache Reservation. read more

A tenuous peace prevailed. Cattle, not the soldiers at nearby Fort Sill to the east of the trail, proved to be the common denominator between fighting men who chose not to fight. Hungry Comanches wanted healthy Texas beef to supplement the wormy flour, the culturally forbidden salt pork, and stringy, diseased beef of their government rations, while the Texans wanted to drive their cattle across the reservation without conflict with the Indians or the Indians stampeding their herds. Most of the time, however, the trail boss of every herd prevented this by offering the Indians a few beeves in exchange for the slow pace of their cattle moving across the lush grasslands of what is now Southwest Oklahoma.

It is perhaps due to the influence of Quanah Parker, former Quahada war chief and, during the time of the Great Western Trail, chief of all the Comanches, that the Comanches did not fight the Texans, though many still held grudges against the white men because the deaths of relatives had not yet been avenged. In 1884, gunfire almost erupted when a group of Comanches demanded horses and provisions from an outfit out of Charlotte, Texas as they crossed the reservation. T.T. Hawkins relates that tensions were lessened somewhat when George Saunders, a fluent Spanish speaker, began to communicate in that language with the leader of the Comanches, who then invited Saunders into his tipi where they settled matters peacefully. The Texan and his Comanche host talked of battles they had either heard of or been involved in themselves between the two former enemies. What could have ended in conflict was settled between two men whose war exploits were highly respected by each. Saunders offered a horse and supplies to the Comanches. After that council ended, "about twenty young bucks," according to Hawkins, "came and helped to swim the cattle across the Canadian River. A number of our horses bogged down in the quick sand and had to be dug out, which sport the Indians enjoyed immensely. When the work was finished, they gave us an exhibition of their riding." The year before, Texas cowboy Daniel P. Gibson met Quanah Parker on the trail at one of the several camps where Comanches gathered. The chief wanted "wohaw, heap fat, heap slick," after which Gibson's trail boss T.J. Burkett motioned for Gibson to do as Quanah requested and cut a fat steer out of the herd. "Hundreds of cowboys knew Quanah Parker," Gibson recalled, "and he had scores of friends among the white people."

In 1878, the year that 75,000 head of Texas cattle passed by Doan's Store on the way to the pens at the railroad in Abilene, Kansas, sixteen-year-old Robert Lemond of Jack County was among the cowboys driving the herds. "The first night in the Indian Territory, the Indians frightened the herd and a grand stampede took place." Trail boss George Atkison told his men not to retaliate against the Indians, but to give them the cattle they wanted after the herd was gathered and shaped up for moving north again.

When old enemies saw each other up close and as fellow human beings on land where the blood of both cowboys and Comanches had been spilled, they could relax and enjoy the fruits of peace, with firearms reserved for game and rattlesnakes, as Texas cattle meandered along the Great Western Trail through the Kiowa, Comanche, Apache Reservation.

Along the Great Western Cattle Trail

Texas trail drivers were engaged in a lucrative business. Learn about their lives, expenses, and potential rewards.

read moreThe 1800's Texans were looking for a way to make a living. There were no markets for the abundant cattle abandoned during the Civil War. The demand of the cattle in the North was high and the North had already established railways to accommodate the cattle, thus the Great Western Cattle Trail was developed on the simple theory of supply and demand.

In 1874 Captain John T. Lytle and several cowboys left South Texas with 3,500 head of longhorn cattle and a remuda of saddle horses. Five years later, the route Lytle cut out of the prairie to Ft. Robinson, Nebraska, had become the most significant cattle trail in history – the Great Western Cattle Trail.

Though less well known than the Chisholm Trail, the Great Western Cattle Trail was longer in length and carried cattle for two years longer than the Chisholm. The Great Western saw over seven million cattle and horses pass through Texas and Oklahoma to the railheads in Kansas and Nebraska, therefore, developing the cattle industry as far north as Wyoming and Montana.

A typical head would move 10 -12 miles a day and included the trail boss, a wrangler, and a cook. The drive from South Texas to Kansas took about two months at a cost of $1000 in wages and provisions. At the end of the trail, cattle sold for $20.00 to $35.00 per head.

Below are sources for information about the price that cattle sold for at the markets on the Great Western Cattle Trail:

The Trail Drivers of Texas, by J. Marvin Hunter, a collection of true accounts of trail driving, by the men who went up the trail.

Quote from M.A. Withers, "I sold the steers to W.K. McCoy & Bros. for $28 per head. I sold a herd of 3,400 two year old steers and heifers to Tabor and Rodabush for $20 per head."

Quote from C.W. Ackerman, "At that time (1873) one thousand pound beeves sold in San Antonio for $8 per head, sold in Wichita, Kansas for $23.80 per head."

The Trampling Herd, by Paul I Wellman. One of the best books written about the trail drives.

Quote from Col. Ike Pryor, one of the great cattlemen of the day, "Thus, cattlemen who paid $8 a head for the steers in Texas, and later sold them at $20 ahead in Kansas had a wide margin to work on."

The Chisholm Trail by Wayne Gard

Chapter V states, "McCoy paid Withers $28 a head for his steers. Extra fine ones as much as $32."

Chapter IX states, "The George Slaughter herd . . . sold for $35 per head."

Chapter XII states, "One of the biggest sales in Elsworth, (Kansas) during the season was that of L.B. Harris of San Antonio, who received $210,000 for 7,000 steers." That is $30 per head.

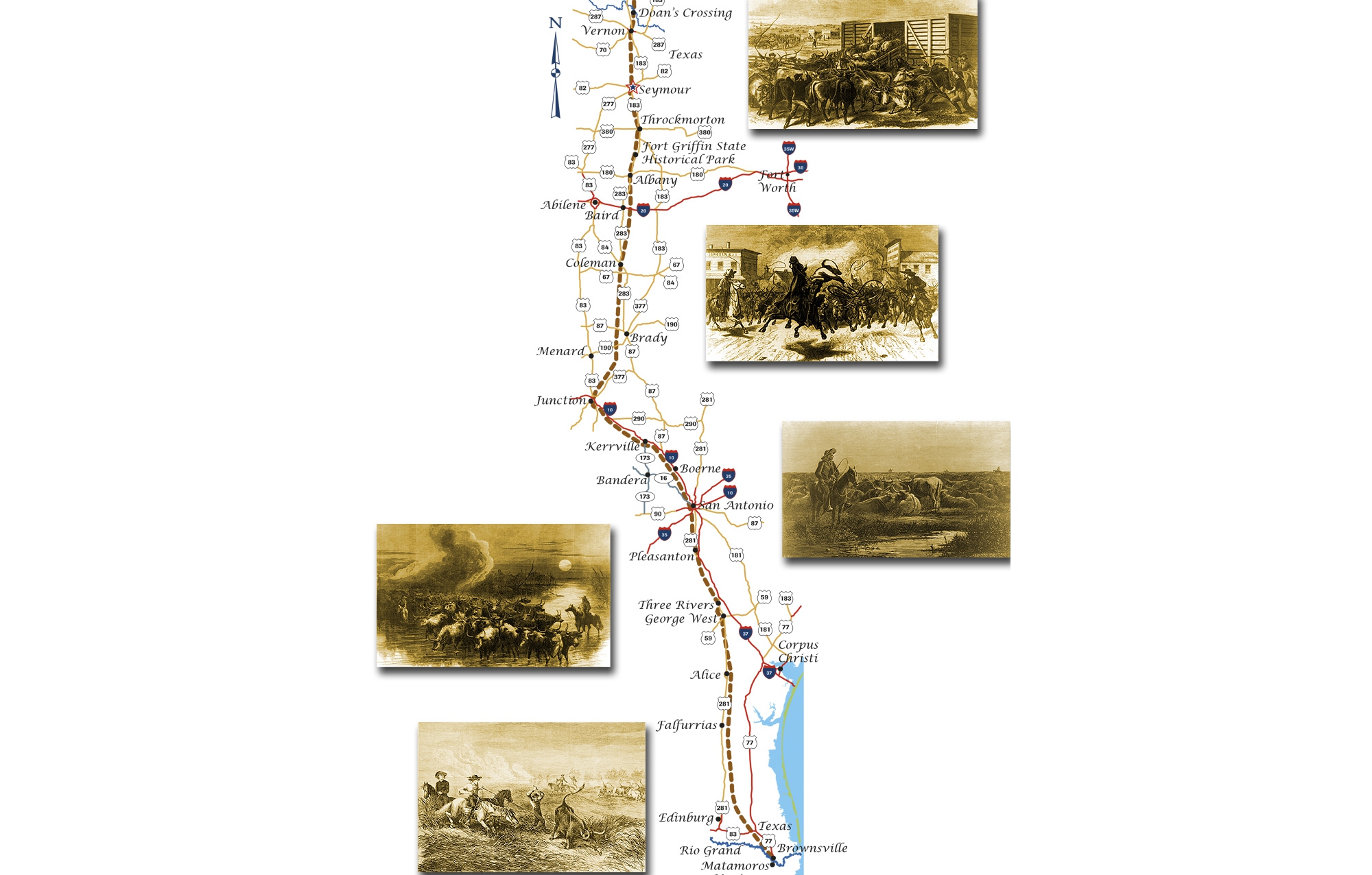

In Texas, feeder trails from the Rio Grande led to the trailhead near Bandera and the Great Western passed through, Kerrville, Junction, Brady, Coleman, Baird, Albany and Fort Griffin. It is believed that the main streets of Throckmorton, Seymour, and Vernon run north and south because of the trail.

Seymour was a major supply center and became a popular campsite for cowboys. Cowboys and Indians alike camped out on the Salt Fork tributary of the Brazos River where Seymour is quietly nestled today. The herds were bedded on high grounds on the east side of the Seymour Creek that runs through the City Park. In 1972 the Seymour Historical Society placed a marker at the northern edge of the community commemorating the trail passing through Seymour. In addition to its 1972 marker, Seymour now has four cement markers more closely marking the trail through Baylor County. The Great Western Cattle Trail entered Baylor County on it southern border along Highway 183. A marker is located at the entrance of the Hash Knife Ranch headquarters where the untamed Millett Brothers Ranch once reigned in the 1800's. The trail lead northward to Seymour Creek on the Salt Fork tributary of the Brazos River. The Vernon Rotary placed a marker in the City park in 2004, near the popular 1800's campsite and watering hole. Another marker was placed on Highway 183 as the trail meandered through rough terrain passing where Lake Kemp is located today. The last marker in Baylor County is located on Highway 183 north as the trail travels toward Vernon crossing Waggoner Ranch, one of the largest ranches in Texas.

Traffic on the Great Western Trail began to decline in 1885 with the introduction of barbed wire. In 1893, the last large cattle drive up the Great Western crossed the Red River, headed to Deadwood, South Dakota. By this time an estimated six million cattle and one million horses had left Texas, crossing the Red River into Oklahoma, as it continued up the trail.

For many years prior to 1896, Seymour had been the rallying point for cowmen from all over the West. A retired cowboy named Jeff Scott broached the idea of a Cowboy Reunion. Scott proposed contests and diversions that vividly recalled old scenes and old associates. The idea "took" and the Cowboys' Reunion of 1896 was organized. 10,000 spectators assembled at the first rodeo and reunion. The following year, 1897, Indian Chief Quanah Parker with three to five hundred of his braves performed war dances for the occasion. The Seymour Rodeo and Reunion continues today, and is celebrated the second weekend of each July.

In 2003 a project was launched to mark the entire Great Western Trail with cement posts being placed every six to ten miles along the trail from the Rio Grande to Ogallala, Nebraska. Oklahoma set the first post south of the city of Altus and challenged Texas to follow suit. The Vernon, Texas Rotary Club adopted the project for Texas. Oklahoma donated the first post in Texas which was set in 2004 during the 121st Doan's May Day Picnic in Vernon Texas. The mold and the challenge was passed on to the Vernon Rotary Club. Through much effort of the Vernon Rotary Club, markers have been placed accordingly across Texas making it easy to follow history down the Great Western Trail as it stood in the 1800's. As you travel the Western Trail today, one can not be amazed how the cattle drovers traversed the different land formations and survived the many adversities to drive 7 million cattle approximately 2000 miles across the United States starting at the Southern most Mexico border leading up to the Northern most Canadian border. Visit the almost mythical cowboy legend trail called the Great Western Cattle Trail, visibly marked for your pleasure.